Ilana Kurshan is the author of If All the Seas Were Ink, published in 2017 by St. Martin’s Press. She has translated books of Jewish interest by Ruth Calderon, Benjamin Lau, and Micah Goodman, as well as novels, short stories, and children’s picture books. Her book Why Is This Night Different From Other Nights was published by Schocken in 2005. She is a regular contributor to Lilith Magazine, where she is the Book Reviews Editor, and her writing has appeared in The Forward, The World Jewish Digest, Hadassah, Nashim, Zeek, Kveller, and Tablet. Kurshan is a graduate of Harvard University (BA, summa cum laude, History of Science) and Cambridge University (M.Phil, English literature). She lives in Jerusalem with her husband and five children.

When I first saw the cover that my publisher had designed for my book, my jaw dropped. It was a lovely image – pages of Talmud arranged to resemble waves in an ocean, neither too feminine nor too scholarly for the audience I hoped to reach. But I was taken aback to discover that the book had suddenly acquired a subtitle – “A Memoir.” Since when was my book a memoir? And what did it mean that I – an inveterate reader of fiction and poetry, as well as a lover of Talmud – had penned a memoir?

In my head I have always had a hierarchy of literary genres. At the pinnacle was poetry. A poet, I thought, is the consummate wordsmith – someone who can distill the maximum amount of meaning per square inch of text. One step below the poets were the novelists, those who take up more space on the page – and more pages – to construct a richly imagined fictional world.

Below the novelists were the writers of nonfiction – those who lack the imagination to create characters and fabricate plots, and so they have no choice but to head to the library, buckle down and research some interesting topic, and write it up. At the very bottom of the hierarchy – or so I told myself – were the memoirists, those who couldn’t find anything interesting they could write knowledgeably about, and so they had no choice but to write about themselves.

I rarely read memoirs, which to my mind seemed almost as worthless as self-help – why read advice for living when fiction, which I always found more pleasurable, teems with the most penetrating and incisive insights into the human mind and the dynamics of human relationships?

I knew that my book was neither poetry nor fiction, though it incorporates lines and passages of both. While I was writing, I regarded my book as a Talmud commentary – my reflections on the page of Talmud I studied each day for seven and a half years as part of an international program known as daf yomi.

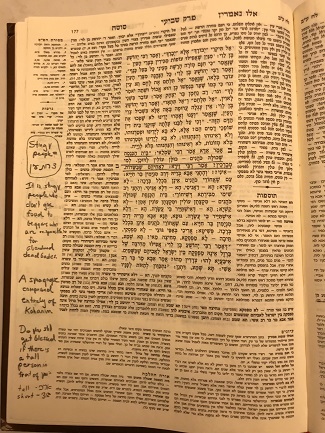

The project that became my book began as a series of notes in margins of the volumes of Talmud I studied: I jotted down question marks where I was confused, exclamation points when something took me by surprise, and boxed summaries of the topics under discussion. When I had more to say than could fit in the margins, I began writing journal entries and blog posts, which I published on an anonymous blog I did not think I was writing for anyone except myself, and so I did not hesitate to write freely about dark personal struggles and deep fears. Had I imagined an audience, I probably would have hidden under my desk, buried my head in my hands, and cringed.

Then five years ago, when I was on maternity leave after the birth of my twins, a friend pointed out that I had one more year left in my seven-and-a-half year daf yomi cycle, and I ought to find a way to mark the occasion. She suggested that I organize all my writing so that I’d have some sort of record of everything I had learned. I opened a new file on my computer and began making lists of all the essays, anecdotes, and poems I’d jotted down or typed up over the years.

Immediately it became clear to me that my writing was structured like the Talmud – I had basically written a book in which each chapter corresponded to another tractate, as a volume of Talmud is known. The book was an extended commentary interweaving the Talmudic text with my own experiences of learning it, such that the text was a commentary on life, and life was a commentary on the text.

It was a long time before I worked up the courage to send off the manuscript into the world. By the time my agent submitted it to publishers, I was nine months pregnant with my fourth child. My agent had promised to call if any publishers expressed interest. Then I went into labor, and just when I entered the delivery room, my phone rang. It was my agent. How could I not pick up? She told me that an editor was interested in buying my book. Really? Could it be? Suddenly my contractions sped up. My husband looked at me quizzically. “Ilana,” he told me, “publishing a book is often compared to birthing a child. But you don’t have to do both at the same time!”

My book, it seemed, was destined to be born. But I was not happy to learn that the same editor who acquired the book was convinced it was a memoir, and that it should be subtitled as such. “Can’t we call it a Talmud commentary?” I pleaded. “Try telling that to my marketing department,” my editor wrote back, and I could imagine the smiley face emoticon.

Then a few weeks after she sent me the jacket image, I read an article in the New York Times Book Review in which Joyce Carol Oates coined a term for a new literary genre: “Rarely attempted, and still more rarely successful, is the bibliomemoir – a subspecies of literature combining criticism and biography with the intimate, confessional tone of autobiography.” That’s it, I told myself. I had written a bibliomemoir! A memoir through books. I could live with that.

And so I’m somewhat of an accidental memoirist, though perhaps it’s ultimately for the best. Many readers – particularly male readers – have told me that they would never have picked up my book had it been fiction. Other people told me how much they admired my courage in being so honest about such deeply personal matters. (“I’m not courageous,” I responded. “I’m just a failed fiction writer who had no choice but to tell it like it happened.”)

Still other readers wrote to tell me that I inspired them to begin learning daf yomi, and that I had developed a new feminist way of reading that Talmud. I’m not sure that’s true. But I do think that had I published my book as a work of fiction – or as a Talmud commentary, for that matter – I would have reached far fewer readers.

My literary hierarchy notwithstanding, I have developed a newfound respect for memoir as a genre. My bookcases now feature a whole shelf of memoirs, in addition to my fiction and poetry collections. I’m still not sure where to shelve my own book, but I trust that eventually it will find its place.

Start the discussion now with fellow book club members – before our book club meeting on September 23!

Join our Mercaz Reads Israel book club book on Facebook, then comment on our discussion questions in the ‘If All The Seas Were Ink’ unit.

In September 2017 Ilana Kurshan’s book of the same name was released to enormous praise. Her beautiful tale of learning Talmud every day is masterful. Her charge to us in this ELI Talk to be open to how our learning can influence our lives and how our lives can influence our learning is nothing but compelling.

Filmed at the William Breman Jewish Heritage and Holocaust Museum in Atlanta, Georgia in cooperation with the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta.